A Small Appreciation of D.W. Griffith

Over the years, I’ve become a fan of the work of D.W. Griffith, one of the pioneers of early film making. Griffith worked with Thomas Edison as an actor and writer, before moving to the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, or just Biograph, as an actor. He complained so much about the directing, that they gave him a chance. This was in 1908. Griffith would go on to make thousands of one-reelers (about 10-12 minutes long) until 1913 when he quit Biograph because he wanted to make longer films.

Griffith’s use of cross-cutting, close-ups, flashbacks and editing allowed him to rise to the top of the directors working in silent film. He had a remarkable cast, too, that began to receive recognition for their work in the films. Such actors as Mary Pickford, Lillian Gish, Mabel Normand, Mack Sennett, Wallace Reid, and many others began, or worked with Griffith at Biograph. Pickford was so popular, she became known as “The Biograph Girl” and parlayed that exposure into a huge movie contract.

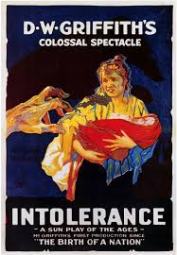

Griffith would go on to make many of the cinema’s greatest films: Way Down East, Intolerance, Orphans of the Storm, Broken Blossoms, and others. The Birth of a Nation became the most successful film in its day, launching the careers of dozens of men who would later become studio moguls, producers and theater owners. (Today, The Birth of a Nation is a pariah in the Griffith canon due to its overt tones of racism.)

(The image on the right is the big centerpiece of Intolerance, with its cast of thousands and huge scenery pieces.)

In 1919, Griffith, Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and Charlie Chaplin founded United Artists, an independent film studio where the producers made the decisions, not the studio heads.

From L to R, Fairbanks, Pickford, Griffith, and Chaplin. At the time, all but Griffith were the biggest stars in the world. Griffith would be the first to sell his interests. Chaplin and Pickford held onto to their ownership of the company until the 1950’s.

(There are two terrific books on the history of United Artists by Tino Balio:

http://www.amazon.com/United-Artists-Volume-1919-1950-Company/dp/029923004X/ref=pd_bxgy_b_img_y

and

http://www.amazon.com/United-Artists-Volume-1951-1978-Industry/dp/0299230147/ref=pd_bxgy_b_img_y

You would think that after making all of these important films, D.W. Griffith would be recognized in Hollywood for the genius he was and he would have lived out his life with the love and admiration of all his peers.

Not so fast. He lived his final years alone, not able to get work, alcoholic, and broke. His films had made millions for others, but he was unable to keep his money. He had often put his own money into his work and lost it when the films didn’t make it back quickly enough.

In 1940, Iris Barry, the first curator of The Museum of Modern Art Film Library, put together a large exhibition on Griffith, with the purpose of restoring the fame and reputation of the director. Griffith was still alive then, and cooperated with Barry on a monograph, short essays, that accompanied the exhibition. It was the first retrospective of Griffith’s career, and one that made the argument that Griffith was not just a pioneer of cinema, but a ground-breaking director, whose films incorporated practically every technique still used today.

I found the second edition of this book yesterday at a used book shop.

The second edition has been expanded because in 1965, the Museum ran another Griffith exhibition and reprinted the original manuscript by Barry and expanded it with a long addendum by the director of the Griffith exhibition, Eileen Bowser. It also has an interview with Billy Bitzer, Griffith’s longtime cameraman.

Griffith died in 1948, alone, penniless. He is buried outside of Louisville at the at Mount Tabor Methodist Church Graveyard in Centerfield, Kentucky. His grave was unmarked for a couple of years, until the Director’s Guild provided a marker. A re-dedication of his grave was attended by Lillian Gish, Mary Pickford and Richard Barthlemess, all who had appeared in Griffith films.

Gish also wrote a book about Griffith, now out of print, but available used.

One last thing, when I was a student at Northern Kentucky University, in 1979, there was a dedication on campus that unveiled a new statue by celebrated artist, Red Grooms. It depicted Griffith directing a scene from Way Down East, with Lillian Gish on the ice floe, and cameraman Billy Bitzer cranking away.

The statue received prominent placement on campus, between the Fine Arts building and the new Student Activities building. I must have passed it a million times, going from one place to the next. I knew who Griffith was, of course, and knew that he had been born in Kentucky, but really didn’t give it much thought.

The artwork was loaned out frequently and when it was returned, it was relocated to another part of campus: the banks of Lake Inferior, behind the Fine Arts building,

As the Grooms artwork remained on campus, there grew an uneasiness about Griffith’s past history with race relations. In 2004, the sculpture was dismantled, where it remains in storage to this day.

Being from the South, Griffith always believed that he impartially showed what happened after the Civil War in The Birth of a Nation. What he didn’t realize was there was a new attitude in the United States toward race. For many people, gone was the hatred, replaced by acceptance. Griffith’s display of race relations in The Birth of a Nation, even though it represented events happening 50 years ago, was not keeping with the mood of the country in present day 1915.

His next film, Intolerance, in 1916, was an answer to those critics, who believed he was intolerant of race. This is Griffith’s finest film, cross cut throughout with four different stories, showing mans intolerance to others always led to ruin. Running over three hours, it was the most expensive film of that time.

Lillian Gish called him “the father of film” and Charles Chaplin called him “the teacher of us all”. Griffith still remains a vital part of cinema history and there will always be film critics and historians trying to determine just how important.

Hollywood loves a story where someone at the height of their career takes a fall. Takes a huge, long, career-busting fall. Maybe that’s why I admire D.W. Griffith. Maybe that’s why I admire Orson Welles. Orson used to say, “Oh, how they’ll miss me when I’ m gone.” And that’s certainly the case. Welles also said, in spite of his own treatment by the Hollywood establishment, “I have never really hated Hollywood except for its treatment of D. W. Griffith. No town, no industry, no profession, no art form owes so much to a single man.”